Desperate parents in Gaza struggle to feed their children as famine unfolds due to an Israeli blockade.

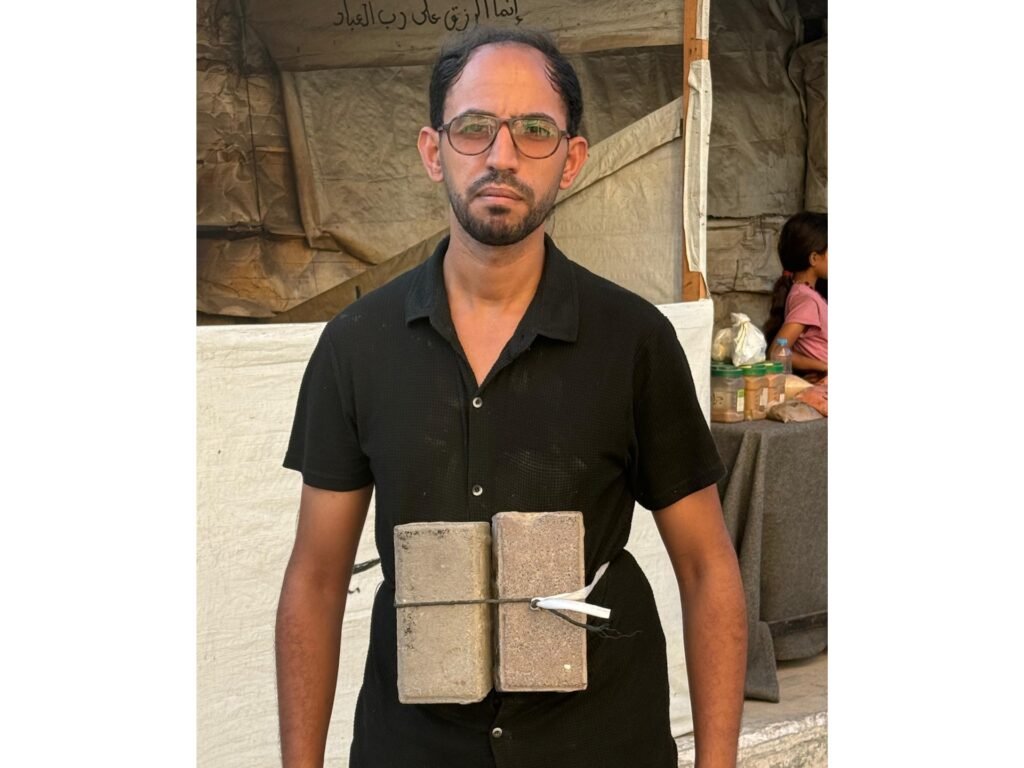

Gaza City, Gaza Strip – Hani Abu Rizq walks through Gaza City’s wrecked streets with two bricks tied against his stomach as the rope cuts into his clothes, which hang loose from the weight he has lost.

The 31-year-old searches desperately for food to feed his mother and seven siblings with the bricks pressed against his belly – an ancient technique he never imagined he would need.

“We’re starved,” he says, his voice hollow with exhaustion.

“Even starvation as a word falls short of what we’re all feeling,” he adds, his eyes following people walking past.

He adjusts the rope around his waist, a gesture that has become as routine as breathing.

“I went back to what people did in ancient times, tying stones around my belly to try to quiet my hunger. This isn’t just war. It’s an intentional famine.”

The fading of Gaza’s heartbeat

Before October 7, 2023, and the start of Israel’s war on Gaza, food was the heartbeat of daily life in Gaza.

The days in Gaza were built around communal meals – breakfasts of zaatar and glistening olive oil, lunches of layered maqlooba and musakhan that filled homes with warmth, and evenings spent around trays of rice, tender meat and seasonal salads sparkling with herbs from gardens.

Abu Rizq remembers those days with the ache of someone mourning the dead.

The unmarried man used to love dining and gathering with family and friends. He speaks of comfortable dining rooms where home-cooked feasts were displayed like art and evenings were filled with desserts and spiced drinks that lingered on tongues and in memory.

“Now, we buy sugar and salt by the gram,” he says, his hands gesturing towards empty market stalls that once overflowed with produce.

“A tomato or cucumber is a luxury – a dream. Gaza has become more expensive than world capitals, and we have nothing.”

Over nearly 22 months of the war, the amount of food in Gaza has been drastically reduced. The besieged enclave has been under the complete mercy of Israel, which has curtailed access to everything from flour to cooking gas.

But since March 2, the humanitarian and essential items allowed in have plummeted to a frightening low. Israel completely blocked all food from March to May and has since permitted only minimal aid deliveries, prompting widespread international condemnation.

Watching children suffer

According to Gaza’s Ministry of Health, at least 159 Palestinians – 90 of whom are children and infants – have died of malnutrition and dehydration during the war as of Thursday.

The World Food Programme warns of a “full-blown famine” spreading across the enclave while UNICEF reports that one in three children under five in northern Gaza suffers acute malnutrition.

Fidaa Hassan, a former nurse and mother of three from Jabalia refugee camp, knows the signs of malnutrition.

“I studied them,” she tells media from her displaced family’s shelter in western Gaza. “Now I see them in my own kids.”

Her youngest child, two-year-old Hassan, wakes up every morning crying for food, asking for bread that doesn’t exist.

“We celebrated each of my children’s birthdays with nice parties [before the war] – except for … Hassan. He turned two several months ago, and I couldn’t even give him a proper meal,” she says.

Her 10-year-old, Firas, she adds, shows visible signs of severe malnutrition that she recognises with painful clarity.

Before the war, her home buzzed with life around mealtimes. “We used to eat three or four times a day,” she recalls.

“Lunch was a time to gather. Winter evenings were filled with the aroma of lentil soup. We spent spring afternoons preparing stuffed vine leaves with such care.

“Now we … sleep hungry.”

“There’s no flour, no bread, nothing to fill our stomachs,” she says, holding Hassan as his small body trembles.

“We haven’t had a bite of bread in over two weeks. A kilo of flour costs 150 shekels [$40], and we can’t afford that.”

Hassan was six months old when the bombing began. Now, at two years old, he bears little resemblance to a healthy child his age.

The United Nations has repeatedly warned that Israel’s siege and restrictions on humanitarian aid are creating man-made famine conditions.

According to the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, only a fraction of the 600 truckloads of food and supplies required in Gaza daily, under normal circumstances, are coming through. The Integrated Food Security Phase Classification system has placed northern Gaza in Phase 5: catastrophe/famine.

Amid a lack of security, the trickle of humanitarian aid allowed to enter Gaza is subject to gangs and looting, preventing people in need from accessing scarce supplies.

Furthermore, hundreds of desperate aid seekers have been shot dead by Israeli soldiers while trying to get humanitarian aid provided by the United States- and Israeli-backed GHF since May.

Abundance as a distant memory

Hala Mohammed, 32, cradles three-year-old Qusai in a relative’s overcrowded shelter in Remal, a neighbourhood of Gaza City, as she describes how she has to watch him cry in hunger every morning, his little voice breaking.

“There’s no flour, no sugar, no milk,” she says, her arms wrapped protectively around the child, who has known only war for most of his life.

“We bake lentils like dough and cook plain pasta just to fill our stomachs. But hunger is stronger.”

This is devastating for someone who grew up in Gaza’s rich culture of hospitality and generosity and had a comfortable life in the Tuffah neighbourhood.

Before displacement forced her and her husband to flee west with Qusai, every milestone called for nice meals – New Year’s feasts, Mother’s Day gatherings, birthday parties for her husband, her mother-in-law and Qusai.

“Many of our memories were created around shared meals. Now meals [have become the] memory,” she says.

“My son asks for food and I just hold him,” she continues, her voice cracking. “The famine spreads like cancer – slowly, silently and mercilessly. Children are wasting away before our eyes. And we can do nothing.”

This piece was published in collaboration with Egab.